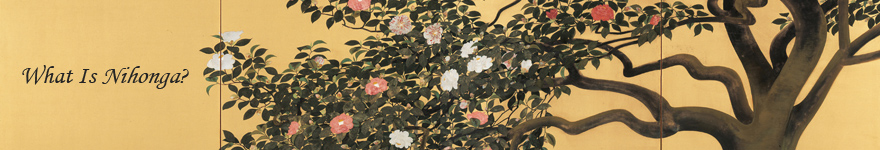

What Is Nihonga?

Nihonga, a general term for traditional Japanese painting, means, literally, "Japanese painting". Now in common use, this term originated during the Meiji period, to distinguish Japanese painting from Western-style oil painting. The distinction between Western-style oil painting and nihonga is thus, broadly speaking, the difference in the painting materials used. While some would argue that anything a Japanese artist paints is nihonga, the distinction based on materials continues to be used.

The term nihonga was already in use in the 1880s. Prior to then, from the early modern period on, paintings were classified by school: the Kanō school, the Maruyama-Shijō school, and the Tosa school of the yamato-e genre, for example. At about the time that the Tokyo Fine Arts School was founded, in 1887, art organizations began to form and to hold exhibitions. Through them, artists influenced each other, and the earlier schools merged and blended. With the additional influence of Western painting, today's nihonga emerged and developed.

Today, however, techniques, sensibilities, aesthetics, and styles based on tradition are changing with the times. Moreover, the question continues to be raised of what nihonga is and whether the distinction between nihonga and Western-style painting has any validity in terms of painterly expression.

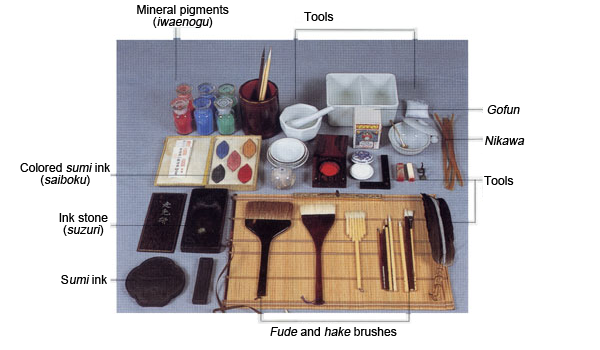

Nihonga materials

Nihonga is based on painting styles that have evolved for over a thousand years. The materials used are also traditional elements developed during that long history. In general, the support is paper, silk, wood, or plaster, to which sumi ink, mineral pigments, white gofun (a white pigment made from pulverized seashells), animal or vegetable coloring materials, and other natural pigments were applied, with nikawa, an animal glue, as the adhesive. Gold and other metals (in gold leaf and other forms) were also effectively incorporated in paintings.

Those materials are not easy to use. Mastering the necessary techniques requires considerable time and determination. Artists continue to use them, however, because the resulting nihonga style suits the natural features of Japan and the Japanese aesthetic sense and spiritual qualities.

<Nihonga materials>

Supports

Silk (kinu): Paintings on silk are known as kinue or kenpon. Silk is one of the most important support materials used in nihonga. The texture of silk, an outstanding material on which to paint, permits a variety of effects through, for example, applying colors or metal leaf on the back of the silk support.

Paper (washi); Paintings on paper are known as shihon. Paper is, with silk, one of the most important support materials used in nihonga. Paper is longer lived than other support materials, and easy to handle. It thus remains the core material for nihonga today.

Pigments

Mineral pigments (iwaenogu): These pigments are produced by finely grinding natural minerals. The size of the particles determines the shade of the color produced. Such pigments can also be roasted to change their color. Nikawa glue is used as an adhesive.

Suihi-enogu: Ordinary soil or clay is used to make these pigments, which are often yellow or red in hue. Nikawa glue is used as an adhesive.

Gofun: The finest quality gofun, a white pigment, now used in Japan is made from natural oyster shells. The term originally referred to white lead, which was imported from China in the Nara period (eighth century). Since the Muromachi period (fourteenth through sixteenth centuries), however, gofun has generally been used to a material based on oyster shells. Nikawa glue is used as an adhesive.

Coloring materials (senryō): These natural dyestuffs are derived from animal or plant matter and used as pigments. Some cannot be used as pigments without modification; in that case, gofun or lime is used to absorb the colors and produce pigments.

Sumi ink: Made mixing lampblack with nikawa glue, it is then placed in a wooden mould and allowed to dry into a stick-like form. To use it, water is placed on an inkstone or suzuri and the sumi stick rubbed on it to produce the liquid ink.

Metallic leaf and paint (haku and dei) : Metals such as gold, silver, or platinum are beaten until extremely thin to produce metallic leaf. Traditional techniques include attaching the metallic leaf as is to the painting and cutting it into thin strips (noge) or pulverizing it into a grainy, sand-like state and scattering on the picture plane (sunago). Metallic leaf reduced to a powder-like form is called dei, which is available in several types, depending on the metal used. Metallic leaf, strips, or grains, or powder are all attached with nikawa glue.

Adhesives

Nikawa: A gelatin made by boiling and extracting protein from skins and bones of animals and fish, it has long been used as an adhesive. Since the pigments used in nihonga have no adhesive strength, the use of nikawa is needed to fix them to the surface of the painting. The two types commonly used now are shika nikawa (industrially processed from cow skin, bones, and tendons) and sanzenbon (which is made by hand, of the same materials). With too much nikawa, the pigment will tend to crack. With too little, it will tend to peel off.

Tools

Fude and hake brushes: Brushes are critically important tools for creating lines and areas of color; their use has a great impact on the resulting painting. They are made of a variety of materials and forms to suit specific applications. Most use animal bristles.

Reference materials

Yomigaeru nihonga--dentō to keishō, 1000 nen no chie (Nihonga renaissance--tradition and succession, 1000 years of wisdom), edited by Japanese Painting (Conservation), Graduate School of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. (Tokyo: The University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts Associates, 2001).

Zukai: Nihonga no dentō to keishō--sozai, mosha, shūfuku (Nihonga tradition and succession--materials, copying, restoration), edited by Japanese Painting (Conservation), Graduate School of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. (Tokyo: Tokyo Bijutsu, 2002).

An Illustrated Dictionary of Japanese-Style Painting Terminology, edited by Japanese Painting (Conservation), Graduate School of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. (Tokyo: Tokyo Bijutsu, 2010).